CHAPTER 14

Joliffe took in that bit of information with a jolt deep in his guts. Was still finding his way to some response when Sebastian said with less satisfaction, “Not that that suffices to prove anything…”

In the early days of new prosperity for Basset’s company, Joliffe treated himself to a small book of poems by Thomas Hoccleve, purchased from a scrivener in London. If you’d not heard of Hoccleve before then, I’m not particularly surprised. Despite his poetry seeming to have been reasonably popular in his own time (born in the late 1360s; died 1426), it afterward fell from notice for a few centuries, was then noticed and denigrated by scholars for a few generations, and only in the latter half of the 1900s began to be appreciated again.

Hoccleve himself admired and knew his contemporaries Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower, and seems to have actually been one of several scribes who copied out some manuscripts of their work. His admiration did not keep him from a personal creative vigor all his own, though, including a wry willingness to write against the grain of fashion. Where it was common practice to set poems in the fair, green days of Spring, he began one long work with:

“After that harvest had inned his sheaves, [brought in]

And that the brown season of Michaelmas

Was come, and began the trees rob of their leaves . . .

And they into color of yellowness

Had died and been down thrown underfoot . . .”

And whereas it was commonplace to have a poem take place as a dream to the poet, Hoccleve instead preferred to keep the moment intensely awake and personal as:

“And in the end of November, upon a night,

Sighing sore, as I in my bed lay,

For this and other thoughts which many a day,

Before, I took, sleep came none in my eye,

So vexed me the thoughtful malady.” [melancholy/depression]

Indeed, he was very much the poet of the personal, to a degree that only the captive Charles, duke of Orleans matched in England at the time.

Hoccleve worked for his living all his life as a government clerk in the Office of the Privy Seal at Westminster, but at some point in his life he had some manner of mental breakdown – “…the substance of my memory, Went away to play for a certain time…” — so severe that it incapacitated him and frightened people away from him. When he recovered, he wrote of that, too – the anguish of losing control of his thoughts, the friends who deserted him, and his struggle to recover, all the while questioning the reason why it happened to him.

Hoccleve seems to me very much a poet who would appeal to Joliffe, both for his wry humor and deep thoughtfulness, as well as for his rich use of words. I personally think I may keep for my own use in moments of severe irk, “Vexation of spirit and torment, Lack I right none. I have them in plenty”!

There’s a quite satisfactory Wikipedia article about him, including a contemporary painting of him presenting one of his works to the future Henry V, and a painting of his much-admired Geoffrey Chaucer that Hoccleve included in a manuscript of his own poems as a “remembrance” of Chaucer for the sake of those who had not known him or had forgotten what he looked like – an endearing gesture on Hoccleve’s part toward a man he never ceased to admire.

There are various modern editions of his works. From my own library, I can recommend:

Hoccleve, Thomas. “My compleinte” and Other Poems. ed. Roger Ellis. University of Exeter Press, 2001.

Hoccleve, Thomas. The Regiment of Princes. ed. Charles R. Blyth. Medieval Institute Publication, 1999.

– Margaret

Follow the virtual bookclub for A Play of Heresy on Facebook and Twitter.

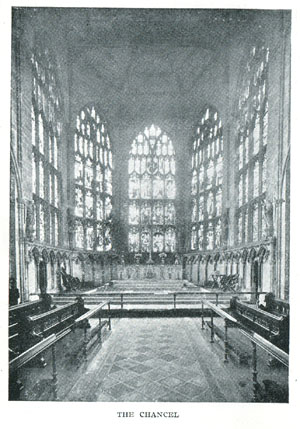

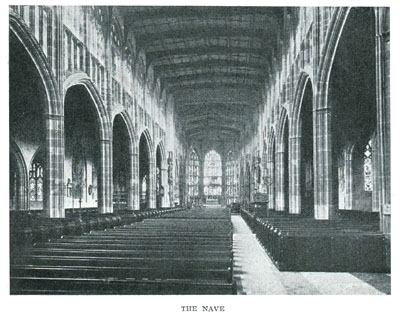

Happily, the age of photography had come before St. Michael’s went.

Happily, the age of photography had come before St. Michael’s went.

Pictures of Fortuna with her Wheel show a beautifully gowned woman, often crowned, often blindfolded, standing beside a giant, upright wheel in her control. Around the rim, small figures of humans cling. Some are obviously being carried upward toward the top of the Wheel where a richly garbed figure is always perched, an obvious winner who has Made It To The Top. But below him, opposite to the rising figures, are figures clinging desperately, head downward and all too plainly being carried down against their will, while at the Wheel’s bottom are those fallen as far as they can go, ragged and impoverished.

Pictures of Fortuna with her Wheel show a beautifully gowned woman, often crowned, often blindfolded, standing beside a giant, upright wheel in her control. Around the rim, small figures of humans cling. Some are obviously being carried upward toward the top of the Wheel where a richly garbed figure is always perched, an obvious winner who has Made It To The Top. But below him, opposite to the rising figures, are figures clinging desperately, head downward and all too plainly being carried down against their will, while at the Wheel’s bottom are those fallen as far as they can go, ragged and impoverished.