CHAPTER 15

The smiths had begun readying their pageant wagon, too, but had yet to roll it out of its shed into the yard. Their shed being higher than the weavers’, they had been able, so far, to work sheltered against the likely chance of rain. With the westering sunlight slanting low and long into the shed, Joliffe could see the steps from the wagon to the ground were already in place and that the stage house’s frame at the wagon’s far end was up. Deeply involved in his own work as he had been, he had not yet taken in much about other guilds’ plays, but here a thick post fixed to one side of the wagon, a high crosspiece thrusting out to one side, could only be the “tree” from which Judas was said to have hung himself in his despair and guilt. That meant the smiths’ pageant must be the Christ’s Passion and Crucifixion…

To put it in brief: We don’t know what they looked like and we don’t know how they were built. Not for certain. Not nearer than reasonable guessing. We know that they were specially constructed for their purpose and were a considerable investment. When the Protestants finally brought an end to performances of the medieval cycle plays, one guild’s account book recorded the dismantling and piecemeal sale of its wagon; apparently it was so specialized that it could not be put to another use as it was.

Other details are gleaned in bits and pieces from other account books and from what the plays themselves obviously required in production, but there is nothing definitive – neither how the wagons looked nor how they were used. Most pictures online and in books are either of much later pageant wagons (take note that Baroque extravaganzas from the 1600s do not accurately reflect medieval stages) – or not wagons at all (they lack wheels and are obviously simply scaffolds, no matter what the label says) – or are attempts at reconstruction by people who extrapolate strenuously, sometimes beyond the evidence, in the attempt to make a medieval pageant wagon that could carry the burden of technological complications the author thinks are required for an effective production, even if sometimes that means adding an unwarranted second wagon.

These latter recreations are done apparently by people without actual theatrical experience, unaware of how little it takes to carry an audience imaginatively anywhere director and cast want them to go, but that is a theme for another essay altogether. Here I have to confess that in writing A Play of Heresy I never had to go into heavy-duty detail on the structure of the pageant wagons or how they looked beyond superficial matters like paint and the position of the stagehouse. The story doesn’t require more than that, and to include unnecessary details would have been self-indulgent.

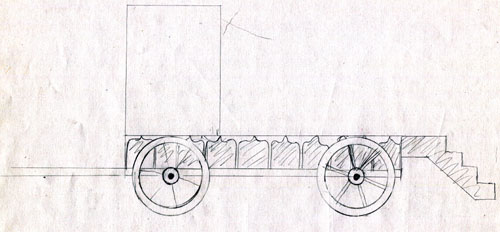

Unfortunately for me, I wanted to understand more. First, there’s the matter of balancing the wagon itself – balance and counterbalance so there’s no danger of tipping. And the position of the stagehouse for at least one of the plays in the book. And size. And proportions. And… And… And…

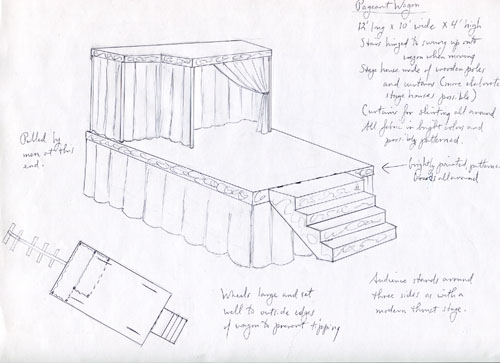

I was working things out in my head at the point when my editor asked if I had a picture of what a pageant wagon looked like. Herewith are the sketches I sent her of my guesses. You can judge for yourself whether they were of any interest to the cover artist, but they certainly served to settle my thoughts as I moved forward with the story.

– Margaret

Follow the virtual bookclub for A Play of Heresy on Facebook and Twitter.

December 23rd, 2011 - 2:38 pm

Interesting!

Somehow I had always envisioned the playhouse/backdrop as being oriented parallel to one of the long sides rather than the short sides. Don’t ask me why, that was just my mental image. Actors would have a bit more playing room sideways, but the stage would have less depth: I’ve never tried to do anything theatrical on a wagon so I don’t know how it would play out in practice either way.

OTOH, the fixed stages I can think of offhand were also at least as deep as they were wide or more so.

December 23rd, 2011 - 5:10 pm

Chris, you probably envisioned it that way because almost all the reconstructions in books show it like that, with the idea that the wagon would have one long side close to and parallel with the houses on one side of the street, and the audience facing the wagon’s other long side. This is derived from the idea that a stage has to be proscenium-style: long side facing audience; audience confined to the front. But we know a great many medieval “theaters” were in the full round and in the equivalent of what are now known as thrust stages. With the latter, the audience can be on three sides, and at the time that was far more traditional than the proscenium notion. So there’s a growing shift among scholars (and very definitely by me) to see the wagons set in the center of the wide medieval street, giving three sides to the audience (as well as two sides instead of just one to those in windows overlooking the wagon) and a long acting area to the performers. Speaking from my own acting experience, this would work a treat.