CHAPTER 9

Cautious to make his curiosity seem light, Joliffe said, “I thought I’d heard Lollards were against plays and players. Mockers of God’s creation. Mockers of the divine. All that manner of thing.”

“They wouldn’t live long in Coventry crying havoc against our plays,” Powet said easily. “Nay, it’s only the worst of them that go that far with things. Same sort as think they can overthrow the king and lords and church and all. I’d guess most have naught against it at all, just enjoy suchlike with the rest of us.”

The town of Coventry was a prospering place in the 1400s, and as was usual in prospering medieval towns, the citizens showed their gratitude to God (and, not so incidentally, their prosperity) by building grand churches. In Coventry’s case, that included three churches with fine spires.

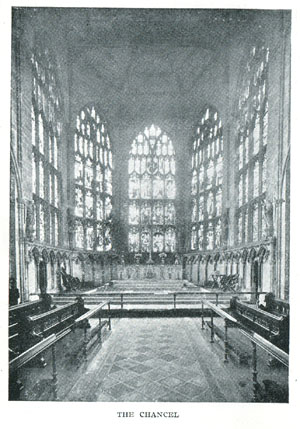

Over the following centuries, Coventry’s prosperity fell and rose in cycles, but always rising proud against the sky above the town were the three spires of its great churches. Of course when Joliffe comes to Coventry in 1438, there are only two finished spires. He sees the third, unfinished, as he approaches the town, and later, he has an assignation in the church there – St. Michael’s, a parish church so grand that when Coventry became a bishopric, St. Michael’s became its cathedral.

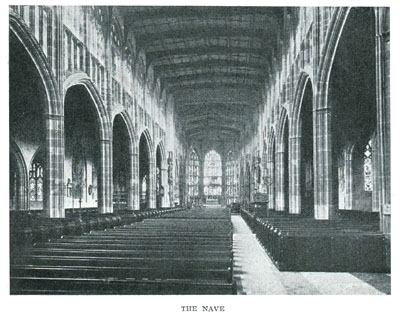

In my travels around Britain, I’ve been in many cathedrals, collecting guidebooks, taking notes, garnering impressions, but although I’ve been to Coventry several times, I’ve never been inside medieval St. Michael’s. It isn’t there anymore. When the medieval heart of Coventry burned in 1940, its cathedral burned with it. The handsome church that Joliffe walks through in A Play of Heresy was hit with too many incendiary bombs to survive even the heroic efforts made to save it. The lead covering the roof melted and ran like rainwater. The carved roof timbers burned and crashed into the nave and chapels. The stained glass windows shattered. The great stone pillars cracked and fell into rubble.

What the people of Coventry did afterward is an inspiration to warm the heart, but it’s not for telling here. Here the question is: If St. Michael’s is gone, what do we actually know of what Joliffe sees there?

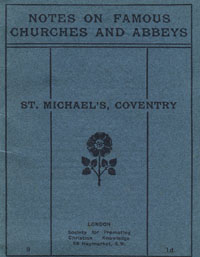

Happily, the age of photography had come before St. Michael’s went. There are useful books and online sites in plenty that show its floorplan and how it was before World War II. For me, though, the source that touched me most deeply came in a fat bundle of little pamphlets from a series called Notes on Famous Churches and Abbeys. Sent by English friends, they include one on St. Michael’s, Coventry, and while other sources had much to tell me, there is sometime particularly immediate in reading words about St. Michael’s written by someone when St. Michael’s was still “alive”, when it was an actual place that could be walked through and experienced, not merely a memory and a regret.

Happily, the age of photography had come before St. Michael’s went. There are useful books and online sites in plenty that show its floorplan and how it was before World War II. For me, though, the source that touched me most deeply came in a fat bundle of little pamphlets from a series called Notes on Famous Churches and Abbeys. Sent by English friends, they include one on St. Michael’s, Coventry, and while other sources had much to tell me, there is sometime particularly immediate in reading words about St. Michael’s written by someone when St. Michael’s was still “alive”, when it was an actual place that could be walked through and experienced, not merely a memory and a regret.

For me, this particularly matters, because bringing alive a past time and place and people is what I try so hard to do in all my books. So much is gone from medieval times, most of it leaving behind far less trace than St. Michael’s has, that the recreating can be laborious, but I’m always glad to do the most I can to make lost places, lost people, lost times seem immediate and real, giving a kind of life to what is otherwise altogether gone.

At Historic Coventry, if you go to the bottom of this page, there is an aerial photograph of St. Michael’s as it was in the late 1800s. Click on the picture to see an identical photo the day after the German raid in 1940.

– Margaret

Follow the virtual bookclub for A Play of Heresy on Facebook and Twitter.

Cautious to make his curiosity seem light, Joliffe said, “I thought I’d heard Lollards were against plays and players. Mockers of God’s creation. Mockers of the divine. All that manner of thing.”

“They wouldn’t live long in Coventry crying havoc against our plays,” Powet said easily. “Nay, it’s only the worst of them that go that far with things. Same sort as think they can overthrow the king and lords and church and all. I’d guess most have naught against it at all, just enjoy suchlike with the rest of us.”

Pictures of Fortuna with her Wheel show a beautifully gowned woman, often crowned, often blindfolded, standing beside a giant, upright wheel in her control. Around the rim, small figures of humans cling. Some are obviously being carried upward toward the top of the Wheel where a richly garbed figure is always perched, an obvious winner who has Made It To The Top. But below him, opposite to the rising figures, are figures clinging desperately, head downward and all too plainly being carried down against their will, while at the Wheel’s bottom are those fallen as far as they can go, ragged and impoverished.

Pictures of Fortuna with her Wheel show a beautifully gowned woman, often crowned, often blindfolded, standing beside a giant, upright wheel in her control. Around the rim, small figures of humans cling. Some are obviously being carried upward toward the top of the Wheel where a richly garbed figure is always perched, an obvious winner who has Made It To The Top. But below him, opposite to the rising figures, are figures clinging desperately, head downward and all too plainly being carried down against their will, while at the Wheel’s bottom are those fallen as far as they can go, ragged and impoverished.