CHAPTER 20

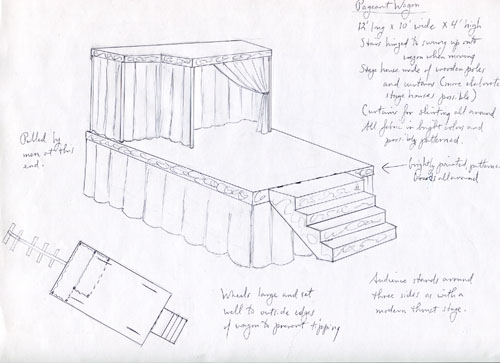

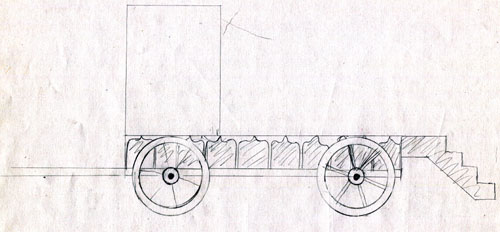

In the Silcok’s yard, standing beside the players’ cart, he considered going up to their room, but it was likely busy with sewing women at present. Sewing and talking. Possibly talking about the murder, so maybe there was something to be overheard and learned, but he was suddenly aware of being greatly tired, and instead of anything more ambitious, he loosed the rear flaps of the tilt, crawled in, and tied them behind him…

I’ve written elsewhere about the joy I take in vocabulary and my ongoing attempts to use words that are pre-1500 in my (especially later) books. So, having come across in this chapter the word “splendidious”, I thought to share some of the vocabulary fun I’ve had over the years (110 double-spaced pages of fun) in my quest for properly medieval words.

To start with “splendidious” itself, it seems I was looking up “splendid” in the Oxford English Dictionary (13 volume edition) to see if it was period. Here’s what I wrote: “splendid: as such no, but ‘splendidious’ and ‘splendiferous’; whee!”

As you can see, I get enthusiastic over vocabulary.

And so, to continue with this peek into my working notes — with the note that anything in square brackets are comments I’ve added here:

abash/abashance/abashed/abashing/abachment: yes [I’m itching for a chance to use some of these variants.]

biscuit: yes, orig. ‘bisket’ — “the senseless adoption of the French spelling with the French pronunciation” according to the OED

chirp: in the form ‘chircle’, yes; see also ‘chirm’

dainteous / dainteth / daintiful / daintily / daintive: yes

daintiness: no; but it’s fairly well the same as some of the above, so go for it

dainty: n.+ adj., yes

enjoyment: no; but ‘enjoyse’ is period and means the same

flagrant: c.1500 and only in the sense of ‘fiery’, ‘blazing’

garbage: as ‘offal’, yes; otherwise, no; try ‘waste’ or ‘refuse’ or ‘rubbish’

handsome: not in looks until late 1500s, it seems, but many other ways; c1430 it was used to mean easy to handle, to manipulate, or to wield or deal with or use in any way [Hmm. So a handsome man in the 1400s would be…]

imp: young shoot of a plant 800s; a child 1300s; child of hell 1500s

jog / joggle: no, but ‘jot’ meant to jog, so I vote for ‘jog’ being okay for a hard-pressed novelist to use

kith: yes; and ‘kith and kin’ and ‘kin and kith’

libidinous: yes, and don’t forget ‘lewd’ and ‘lecherous’

marbles: the game, not by this name; ‘boules’, ‘bowles’, ‘bowlys’, knikkers’ (from the Dutch), and ‘billes’ (in France) all seem to be period.

nervous: in current sense, late 1700s; in sense of having strong sinews, yes; “sinewy, muscular, vigorous, strong”

occasional / occasionally: no, but Pecock uses ‘occasionarily’ in this sense, so close enough for me

plot: as small piece of ground, yes; n. otherwise, no, but the form ‘complot’ is period; v. no

plotter: no, but ‘complotter’?

quarrelous: yes [And of course in any murder mystery you need at least one quarrelous person, yes?]

rascal: 1300s; a raskyl of boys [So useful around Piers!]

scribble: yes. c.1465 Plumpton Correspondence: “scrybbled in haste with my own hand in default of other help”

tousled: yes; ‘touse’ is to handle roughly; drag or push about; of a dog, to tear at, worry

unconcious: not until 1700s; try ‘insensible’

vengeance: oh, yes, no trouble. Also venge, vengeable, vengeably, vengeant, vengement, venger, vengeress (name of a spear c.1450), vengesour. But not vengeful; go figure.

whore / whoredom / whorehouse / whoreson: yes. Not so incidentally, “horeling” is someone who is a fornicator, whoremonger, adulterer, paramour. [And by the way, “ho” was a medieval slang word for “whore”. But I’d never get away with using it.]

yammer: yes

Alas, somehow I’ve never had occasion to question a word beginning with an x or z, so here I make an end.

– Margaret

Follow the virtual bookclub for A Play of Heresy on Facebook and Twitter.